Monumental Cemetery of Milan

About 25 years ago, I started playing a computer game called “Civilization”, which was released by MicroProse, a company founded in part by a man named Sid Meier.

Meier is a historian and musician as well as a computer programmer. So this particular game really combined a lot of his interests and talents. By today’s standards, many kids would consider it a total bore: it’s a thinking man’s strategy game about slowly building a civilization.

One of the many things the game did well was to simplify (but not overly simplify) how scientific observation and knowledge built on itself over time to allow for more discoveries, greater creations and achievements, and of course, more horrific wars.

One of the very early things your civilization’s scientists could “discover” was ceremonial burial.

Now at first, this seems a bit odd, because ceremonial burial really isn’t what one might think of as a scientific accomplishment – and perhaps it’s not. (Though there was definitely some early science behind the embalming and mummification of Egyptian nobility thousands of years ago.)

Regardless, ceremonial burial was one of the early signs of respect given to our fellow humans. For even though the dead are (as far as we know) unconcerned with their own earthly remains, somewhere along the line of human development, we felt that something should be done to return the body to the ground in a respectful way.

This led to philosophy: why do we even exist, if only to die? Do our lives even matter? If so, in what way? To whom? Why?

All questions explored by better philosophers than myself.

Philosophy branched off into religion, which tries to answer some of these questions through faith, as opposed to strict reason.

In the summer of 2017, my wife Isabella and I returned to a place we hadn’t been in twenty years: Il Cimitero Monumentale di Milano (The Monumental Cemetery of Milan). It’s monumental in size, yes, but it’s also known for the large number of actual monuments that have been constructed to serve as graves and familial tombs over the last two-hundred-plus years. Isabella and I spent at least an hour and a half there on a very hot day, just looking, talking, and thinking.

Here is ceremonial burial at its height. Many of these tombs are ostentatious and perhaps even garish to outsiders, yet lovingly justifiable by their families.

Isabella's great grandmother is buried here, but I never knew her. Consequently, I was experiencing this place with no personal ties to it. This freed my mind to follow the well-worn paths of – as I said earlier – much better philosophers than myself. It gave me time to reflect on life, death, and this odd, long-standing tradition we have of preparing a dead body, having a celebration or service for the person that it once was, then memorializing it in some way.

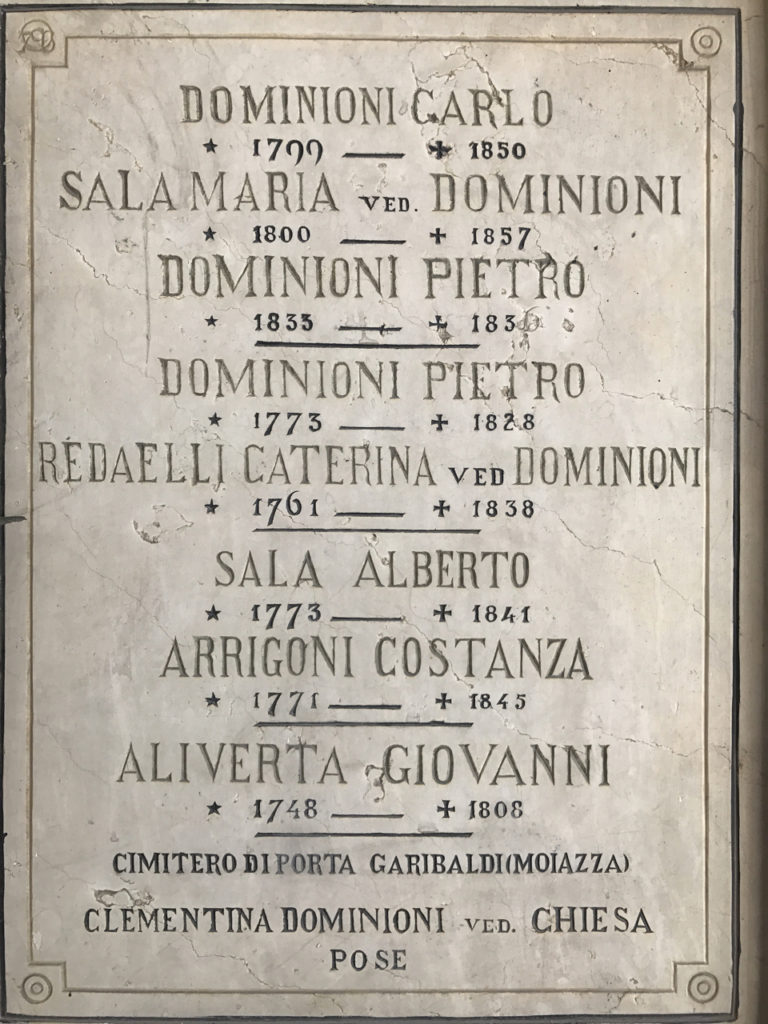

In the following photos that I curated for this post, I’ve refrained from writing comments or captions, save for the last two images. I also have decided not to provide translations wherever words are visible. I know the inscriptions on these tombs are in Italian, but I doubt you need to be told, for example, that one grave expresses how a family grieved the loss of two brothers, two days apart, in the same battle in World War II. Or how another was lost at “barely twenty years old” during World War One. I’m hoping all of these smaller pictures will make a bigger picture for you to think about, as I did that day.

Some of the tombs are enormous paeans to the people whose remains are within them. One must have a key to enter these small buildings, and inside, one can see that entire generations are entombed together: ancestors who purchased these plots had the foresight and desire to keep family members they would possibly never know close to them, even in death.

Other graves are decorated with ornate and intricate sculptures which were in some cases created by artists who were very well-known in their time. There are a few of these which I found deeply disturbing, yet I sense that I felt exactly what the family wished to convey at that moment in time, whether it was profound and indescribable despair or an unappeasable anger at the untimely death of their loved ones.

Some have simply been forgotten over time. With greenery now growing over them, their inscriptions and dates are rendered unreadable by centuries of erosion, the gravestones themselves slowly being swallowed into the ground to join the remains they mark. Perhaps the family line had come to an end and no one was left to pay for upkeep. Perhaps their descendants had moved on to other countries. Perhaps these ancestors were just forgotten...

In the Judeo-Christian faiths, the book of Genesis states, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return.”

This sentiment has become part of the “From ashes to ashes” liturgy used in our modern-day ceremonial burial services.

Both the religious and atheists alike may find comfort in the similar sentiment by famed astronomer Carl Sagan who, in part of his brilliant introduction to “Cosmos”, stated, “The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star stuff.”

We cannot be destroyed, not completely. Some part of us will always be floating around the universe. It’s one of those rare points where faith and fact seem to meet quite comfortably.

So, is there any reason that some of these graves are for babies who died at birth along with their mothers, while others are for men and women whose lives spanned nearly a century? Was the life of the soldier who was cut down in youth any more or less important than the life of the doctor who lived longer than so many of his patients?

If brevity is the essence of wit, then this quote, often attributed to Charles De Gaulle, sums it up most briefly:

“The cemeteries are filled with indispensable men.”

However, a writer named Elbert Hubbard (no relation to L. Ron) is more likely the source, and his version was expanded upon in several publications. This 1909 Abilene (Oklahoma) Reporter newspaper variation on the thought appeals to me for its unapologetic honesty:

“Young man, as you perambulate down the pathway of life toward an unavoidable bald head bordered with gray hairs, it would be well to bear in mind that the cemeteries are full of men this world could not get along without, and note the fact that things move along after each funeral procession at about the same gait they went before. It makes no difference how important you may be, don’t get the idea under your hat that this world can’t get along without you.”

Please keep all of this in mind as you look through my photos. Remember that these were all people who were loved or respected, or if they were lucky, both. The series starts with two shots of the entrance to the cemetery and moves on from there. Pay special attention to the two photos which I placed last in the series. I believe they may be key to some truth our civilization is still seeking.

Surreal