A Jewish Soldier in WWII

On July 22, 1944, about seven weeks after the beaches of Normandy had been taken in D-Day, the 28th Infantry — the “Iron Division”, as World War One’s General Pershing named it — landed on that same beachhead.

The men had trained first in the American South under the command of Major General Omar Bradley, and then prepared in southern Wales by Major General Lloyd Brown for a post D-Day mission known as “Operation Cobra”.

After Normandy, the 28th pushed east towards Paris, following roads littered with the horrid refuse of war, both mechanical and human. They occasionally engaged in combat to keep this path cleared for more American forces coming behind them, then helped surround the final German position (the German Seventh Army) in Northern France in what was called the “Falaise Pocket”. The eradication of this pocket in little more than a month after landing at the beachhead officially ended the longer campaign of the Normandy Invasion.

From there, the men of the 28th became part of the 15,000 Allied soldiers to enter Paris, and were given the honor of marching down the Champs-Elysées on August 29, 1944, in what is officially considered the Liberation of Paris.

Somewhere in the photo of those soldiers is a man named Morris Vinar. He was my mother’s biological father. He served under great generals. He was sent to Normandy to finish clearing a path to Paris. His division was given a hero’s welcome after doing its part to liberate Paris. He was a Jew.

He had about 100 days left to live.

That’s because, liberations and celebrations aside, the war was far from over. After perhaps a week in Paris, the 28th was directed to the German defensive region called Westwall. To the Allies, this defensive position was known as the Siegfried Line, but by any name, it was a formidable obstacle to the penetration of Germany. Nearly 400 miles long, it stretched just inside Germany’s western border from The Netherlands in the north to the Swiss border in the south. Aside from its often unforgiving terrain, this line was heavily fortified with barbed wire, mine fields, manned bunkers, anti-aircraft turrets, and tank traps known as “dragon’s teeth”. Worse, many of these traps were soon to be hidden by a layer of snow. It was along the northern edge of this line that the 28th, with the grandfather I would never know, engaged in the Battle of Hürtgen Forest, inside Germany, near its border with Belgium. According to a book with the unfortunate title “More Military Blunders”, this was the longest battle on German ground during World War II, and is to this day the longest single battle the U.S. Army has ever fought: it lasted from September 19 to December 16, 1944 — nearly four months. Some sources consider that the campaign actually lasted into Spring of 1945, when the Allies finally crossed the Rhine.

Westwall had been planned and built by the Nazis between 1936 and 1940. So by the time the American 28th Infantry Division arrived in Hürtgen Forest in September of 1944, the area was filled with every imaginable type of booby trap and horror that the minds of war could devise. One of these marvels of murder was known as a “tree burst”.

A Wikipedia entry states: “Tree bursts is a technique of using air bursts by timing artillery shells set to go off in the treetops. This causes hot metal shrapnel and wood fragments to rain down. Since American soldiers had been trained to react to incoming artillery fire by hitting the ground, the technique proved particularly deadly.”

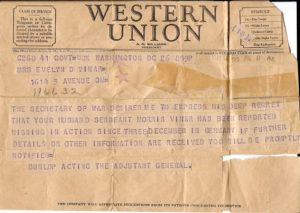

It was thus that Sergeant Morris Vinar was killed on December 3, 1944, his helmet bashed by shrapnel. He may have been shot before or after this tree burst as well.

By the time the collective battles along the Siegfried Line ended, 140,000 Americans had been killed.

Re-read that. The number is correct.

Sergeant Vinar was buried in Allied territory, in the American Cemetery of Margraten, The Netherlands, where he rests today. At first, his grave had been mistakenly marked with a cross. A letter my brother Adam possesses apologizes on behalf of the U.S. Army, and states that Morris’s headstone had been replaced with a Star of David.

My mother was born exactly nine months before the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Her father was drafted, trained, and sent to war some time after her second birthday. He was dead before her fourth birthday, killed in action only thirteen days before the end of that four-month-long Siegfried campaign in which he fought, and only five months before V-E Day.

If, if, if…

On this day, I can’t “remember” a man I never met and of whom my own mother only had a handful of memories. I can look, though, at the Silver Star and Purple Heart he was awarded as part of the 28th Infantry Regiment – one of the most decorated regiments in the U.S. Army – and be thankful that like millions of men before him, he did his part to ensure freedom in our own country. This, I will remember every Memorial Day.

Most of all, though, I want others to remember that Jews were not all just helpless victims of the Nazi war machine. More than half a million American Jews fought in WWII. Many, like my grandfather, were killed in action. He was awarded twice for his bravery. He died for his country. He left loved ones behind.

To this day, groups of young people all over The Netherlands and Belgium pitch in to sponsor the graves of the American soldiers buried in Margraten. They help keep the graves clean and decorate them with flowers from time to time. I was for a while in touch with one such man, Desire Philippet, who took the picture of my grandfather’s grave that you see here.

Morris Vinar’s Headstone

Credit: Desire Philippet

Comments or corrections? Please contact me.

Consciousness

You May Also Like

The Morality of Eating

June 10, 2018

Brevity

October 24, 2018