Quarantine Cyberterrorism

A number of years ago, I was hired by an IT firm to help test their network defenses at a secure facility. I went on-site in plain clothes, sat in a public area, got on the public WiFi, and attempted to hack into the private network from there. I tried to access the web interfaces of the firewall and WiFi router. I tried to guess passwords, gather info about the IP addresses of servers, and used other basic hacking techniques. I found an unmonitored ethernet port on a wall and jacked into it, but was not connected to the network. I did the same on another port, and was again denied access. All of my on-site efforts were, as expected, unsuccessful.

I was able to find an IP address, though, which I could try to penetrate from outside. For at least twelve hours, I ran a dictionary-style, brute force password attack against their firewall – hundreds of thousands of passwords were attempted overnight. The only issue I found here was that my IP address from home should have been blocked after several incorrect attempts, but wasn’t. Regardless, I was unsuccessful at getting in.

Finally, I tried a lower-tech approach.

Since the IT services for this facility were part of a public contract, the awardee’s name was public knowledge. This was important to establish in order to illustrate that I wasn’t operating on privileged information, as the awardee was the one that hired me.

I went to that company’s website, and copied their logo from their home page. I quickly laid out what looked like a respectable name tag, printed it onto a sticker, and put it on a badge with a lanyard. I drove myself to the facility again, put on my name badge, and went upstairs to the main offices. I introduced myself to a lady at the front desk, smiled, made a joke about being the new guy, showed her my badge, and said I was there to work on the server.

She let me right in.

If this sounds exceedingly clever to you, I can assure you it’s not. In the world of information security, social engineering is usually the easiest vector to exploit. People can be fooled. Computers, not so much.

Which brings me to a bothersome trend during our coronavirus quarantine: the increase in threatening emails demanding payment in Bitcoin, in exchange for not sharing information the sender purports to have about you — blackmail in the vein of “Black Mirror”. Here’s an actual, kind of scary example a friend recently received and forwarded to me:

I’m going to make you a one time, non negotiable offer.

?’? aware that “mittens” is ?our passwor?.

I requi?e your 100% atte?tio? for the upcoming ?4 ho?rs, ?r I will ce?tai?ly make s?re yo? that ?ou ?iv? ou? of emba?rassmen? f?r the ?est of yo?r lifetime.

H?l?o, you do not know me. Y?t I k?ow ju?? ??out eve?y?h?ng c??ce?ni?g ?ou. Your f? con?act list, smar?phone contacts plu? ?ll the onli?? activit? in y?ur ?o??uter f?o? previous 113 days.

Includi?g, y?u? masturbation ?i?eo f?otage, wh?ch ?rin?s me t? th? primary moti?? wh? I a? craftin? ?his s?ecific m?i? to you.

W?ll t?e la?t ?ime you ?ent to s?e th? adu?t mat?rial w?bpages, m? spyware ?as t?igg??ed ?nside y??r comp??e? ?y??em w?ich en?ed u? loggin? a ?y?-c?tching ??deo footage of your se?f pleasure ??ay s?m?ly by activating your web c?m.

(yo? got a incred?b?y ?dd ?aste btw ??fao)

I o?n the comp?et? rec?rding. ?n t?e cas? you fe?l I am mess?ng around, simp?y r?ply proof and I wi?l be ??r???d?ng th? ?arti?ula? r?cordin? ra?dom?y t? 3 p??pl? ?o? ?ecog??ze.

I? mi?h? be ?our fri?nds, ?o workers, boss, mo?her ??d father (I don’t kn??! My software wil? ra??omly ??lect the c?nta?t deta???).

W?l? you be ?apa?le ?o ga?e i?to a??one’s eyes aga?? a?t?r it? I doub? i?…

?onetheless, ?t d?e?n’? hav? to be ??at way.

I’m ??i?g ?? ?ak? you a ?ne tim?, non n?gotiable offer.

Purchase ?SD 300? in BTC and sen? th?m on ??e ?own ?elow ad?re?s:

**2TvsLY1KX7ZPeLD3SF1KJL**rxqRgJJptcs

[CASE-s?nsi?ive s? copy & paste it, an? ?e?ove ** from it]

(If you don’t k??w how, look online how to a??u??e BTC. Do not w??te ?y imp??ta?t ti?e)

If you send out t??? pa????u?ar ‘donation’ (??t us call ?t tha??). I??ediatel? aft?r t?a?, ? wi?l vanis? ??d u?der no ??rcumstances c?nta?t you ?gain. I w?l? ?el?te e?e?ythin? I have got abou? ?ou. ?ou may carry o? ?ivi?g your current ordin?ry ?ay t? day lif? wit? no co?cerns.

?ou’ve go? 2? ??urs in order to d? ?o. Your ti?? starts as soon yo? go through this e mail. I hav? go? an special co?e that will noti?y me ?s so?n as you s?e this e mai? so d?n’? tr? to ?la? smart.

Creepy, right? Fortunately, these are almost always fake (although, the ransom-style font is certainly a nice touch on this one, isn’t it?). The brilliance of this scam is multifaceted. I’ll break it down here and explain why you can rest easy and ignore it:

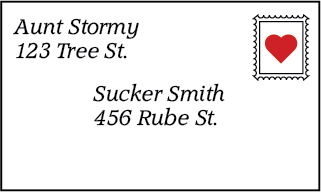

• Sometimes, the email will appear to come from a friend — or even from your own mail account.

The “From” line in an email is quite easy to fake. The real information is carried in the “header” of the email. This data is generally hidden from view because it contains information about the origin and route of the email prior to getting to you. It’s similar to how you can track a package as it’s delivered from one facility to the next, until it’s brought to your door and you sign for it. Most of us don’t really care about this (unless there’s a problem), so we don’t see that information. However, if you look at an email header, you can see that while the sender claims to be Aunt Stormy’s Comcast account, it really started from a server in Russia (or Ukraine, Brazil, China, India, or a Nigerian prince – choose one) and is clearly, to the trained eye, not from Aunt Stormy, and not even from Comcast. When an email doesn’t seem right to you, this is almost always the case. (Note: There are plenty of cases where someone’s email account is legitimately hacked, but that’s for another time. We’re concentrating on cyber-blackmail in this post.). To the point: the forged email address is no different from the fake name badge and lanyard I made.

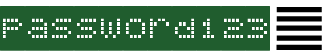

• In some cases, the would-be hacker has supplied an actual password of yours as proof that everything else they say is true, heightening your alarm.

You are likely aware of the numerous data breaches over the past three years or so: Wells-Fargo, Equifax, Adobe, eBay, LinkedIn, Zynga, Marriott —just to name a few. Almost no individual has been spared exposure of their personal data (not to mention what we share willingly via social media). In these breaches, sometimes very important information, like social security numbers or driver license numbers, are compromised. In the majority of cases, though, most of what’s taken includes names, addresses, email addresses, phone numbers, and occasionally passwords and the answers to your security questions. When a would-be hacker or cyberterrorist has these things, they can contact you and give you just enough stolen personal information to make you pay attention. It’s easy to believe someone has been using your computer’s camera when they have presented you with a password or security answer you’ve used before. It was easy for the lady at the front desk to believe I was there to work on the server, because my knowledge of the correct IT company was like a password; it conveyed legitimacy.

• The menace assumes you are uneducated about technology and will believe anything that they assert is not only possible, but has already happened.

The use of a thing does not require intimate knowledge of how to build or maintain that thing. So it is with computers. Most people know how to use what they like on a computer: email, social media, shopping, word processing, etcetera. But if someone tells you they can control your computer’s camera without your knowledge, you simply don’t know enough about how it works to know if it’s possible (it is), much less what would be required to do it (a lot of things). Don’t let ignorance be your enemy by heightening your concern and making you do something ill-advised. While I did not have to deploy this tactic, I was prepared to: if the front desk woman had hesitated, I was ready to say that I feared their data might be irretrievable if I didn’t get to it right away. I would have used her (presumed) ignorance of a situation to assert my importance and authority.

They don’t know anything about you apart from whatever data was revealed in a security breach — and the likelihood that you have masturbated.

• Cyberterrorists prey upon very real human concerns, often delving into sexual preferences. They make you feel violated not only regarding the data on your computer, but also regarding private moments that they want you to believe were not private.

This the most insidious part, right? I saw you masturbating. I know what you like, and dude, there’s something wrong with you! Pay me, or everyone you know will find out about this.

It’s one of our most base fears, not unlike the dream where you show up to school or work with no clothes on: private moments made public. Cyberterrorists know this; it’s why they use it to motivate you into sending them money. This is the social engineering I was talking about earlier, flipped on its head. Where I used a smile and an easy-going demeanor to make the front desk person at that facility trust me and let me in to their server room, these people use fear and threats — and they use them about a subject they know most people find off-limits: our sexuality. But here’s the truth: on “Top 10” most visited website lists, pornhub.com is always there. Always. Many, many more people view and enjoy pornography than are willing to admit it. Furthermore, the sheer size of categories alone speaks to the wide variety of things a person might find sexually arousing. However, it’s this very categorization that makes a person feel that their tastes are somehow marginal to society’s — and the terrorist counts on this. You read, “yo? got a incred?b?y ?dd ?aste btw ??fao”, but you think you read, “I know you like dressing up like Homer Simpson and wearing a diaper, and I’ll tell everyone you know about it.” Their power is in their vagueness. They don’t know anything about you apart from whatever data was revealed in a security breach — and the likelihood that you have masturbated. If you stopped to think about it, you’d know that. Unfortunately…

• They give you very little time to act.

This is the pressure point, right here. You have 24 hours to pay me, or else. They have claimed to have compromising video (or still images) of you doing something they’ve convinced you to be embarrassed about, and they will use it if you don’t pay them. It’s at this point you should realize that they have offered no proof of their claim. They’ve made vague threats with vague data, but it scares you because you are a human living in the 21st century. How well do you respond to pressure tactics at a car dealership? You should respond with even less urgency to something like this.

In summary: The “From” address on these emails is fake. If they presented you with one of your passwords, it was likely stolen in a data breach. They suspect you don’t know enough about computers to question them. They make a pretty safe assumption that you have occasionally viewed pornography and enjoyed it. Finally, they pressure you into moving quickly, before you have a chance to realize it’s a scam. And that’s the truth of it: you should treat anything like this as a scam, and act accordingly: trash the message and don’t look back.

That is, unless they sent a video or image of you from your computer’s camera. In that case, you’re a total freak, and the only person on earth who masturbates. Pay the ransom.

That’s a joke.

As for my great, socially-engineered hack? I was eventually caught, after about ten minutes of playing on that network — more than enough time to have caused real problems or to have copied data. Fortunately, I had the name of someone on the inside to vouch for me before they hauled me off in handcuffs.

Oooh, handcuffs….

Illustrations by Adam Junkroski

You May Also Like

First, Mankind

October 19, 2018

On the Twentieth Anniversary of My Father’s Death

September 1, 2019